“I want to make a game to teach these online students about international trade.”

It’s late 2013 and the LI eLearning team are on Skype with Dr Mauricio Marrone from the Macquarie University Faculty of Business and Economics. Mauricio is a mellow and reasonable guy. He makes everything sound easy.

When you say teach about

international trade...?

Concepts like supply and demand,

comparative advantage, price determination,

cartels, collusion, that sort of thing.

That sounds awesome. Complex. Meaty. But there'd be a lot of ways to approach it. Do you have a particular game style or mechanic in mind?

it'd be something like

Settlers of Catan!"

I love it! Let’s do it!

Not so fast: The hidden complexities of games

Here’s the thing with games: we tend to overestimate the fun of playing them, and underestimate the complexity of developing them.

Just because something is a game doesn’t mean it’s fun; go to any games retailer and you’ll see a bin full of games nobody wants to play because they’re tedious, complicated or they look dated.

And the complexity of game design sneaks up on you. Even if you have a simple core mechanic, you realize very quickly that there is far wider range of possible system and user behavior in a simple game than you would find in an simple website or application with a more linear, predictable flow. Balancing and tweaking rules takes time, and testing the possible variations in user behaviour can become a surprisingly large QA task.

So while on the surface Mauricio’s game sounded awesome — a rich domain, multi-player play, lots of potential rules and mechanics — we needed to find a game design that would work, be affordable and achievable, and we needed to find it before we started development. We were going to need a way to manage the risk inherent in product design.

Finding the fun:

Paper-based prototyping

Mauricio had already worked out a basic rule set for his game. “You can buy and sell resources, and if you have the right tools you can process those resources into goods which you can sell to the bank. Game lasts for 30 minutes, and whoever has the most money at the end wins.”

He held a sheet of paper up to the webcam and showed us a table of pictures and numbers. It looked like a good start.

Can you send us a copy of that?

With any game idea, the first thing you need to do is figure out if it’s fun to play. For action games, this means making a digital prototype because you need to actually get a feel for jumping or shooting or whatever, but luckily Mauricio’s game was negotiation-based so we could work on paper.

We put Mauricio’s rules to the test both at our homes and in the office, tweaking and experimenting with variations on the rules that Mauricio provided.

The results were inconclusive. The first problem was that the winning and losing strategies seemed too obvious, which was a serious problem for replayability. The second problem was that it wasn’t clear if there were any real insights into international trade coming from playing the game.

A week later we were back on the phone to Mauricio, questioning everything from fundamental parameters (“Is this turn-based or simultaneous play?”) to additional wrinkles (“Should there be randomized events that pressure players into certain types of trades?”). We had lots of questions, but nobody could agree on answers. We had increased complexity, not reduced it.

This time with feeling:

Student-based prototyping

We decided that what we needed was a controlled trial of several versions of the game, using the actual target audience.

Mauricio bribed about 30 students into attending four separate playtest sessions of his draft rule set, and our design team flew down to Macquarie University to observe.

The sessions were everything you want from a playtest. Mauricio projected rules up on a wall, talked through the player objectives, handed out sealed envelopes with each players’ allocation of resources and capital, and then he let them loose on each other.

The a-ha moment:

What’s this game really supposed to do?

What really jumped out from these trials was that the strength and value and fun seemed to come from haggling under pressure. Watching students when they were playing simultaneously, in real-time, and with limited information about player resources — it was like watching people in a street bazaar or an 80s-era stock trading pit. They were hyped and engaged, panicked and desperate. It was great.

After the final student playtest, we retreated to a faculty office to debrief. It was clear that turn-based play was too slow; all the fun was found in the panic and desperation caused by real time-play with traders jockeying for each other’s attention. On the other hand, this meant that there would be little time for reflection and thinking about principles of international trade — would that diminish the educational outcome?

After some discussion, Mauricio reached a decision:

Learning the principles of international trade is not the main objective. The main point is to break the ice. After the game, we can ask students to reflect on their actions, behaviours, and learning outcomes.

That’s a big shift in direction. Are you sure about that?

Mauricio was sure. “We’re about to launch our faculty’s first online course. We’ll have fee-paying students from around the world, and one thing we know is drop-out rates in these online courses are really high. If we can give the students a great experience in the first week, something that says this is going to be an interesting course, something that helps them meet some of the other students online, build relationships, that’s the main thing. We can talk about some of the economic ideas behind the game when they come up later, but we don’t need to see this as a way to practice applying theories or strategies. They’re only going to play it once. Let’s keep it simple. Let’s make it about meeting people.”

Learning through sketching

The trick with any interface is to start drawing. There is more than one devil in the detail of systems design, and when you sit down with a couple of people and sketch out each part of the experience, trying to imagine what your audience will be doing at each step of the way, you can solve many problems before they even appear

In the case of the trader game, we’d already done so much thinking that the first round of sketches was very quick.

We started by saying chat would be key: players needed to be able to communicate in real time. But what kind of chat? Video? Text only? How many chat windows would you need? How many types of conversations would you be having at once? Guiding all this was the sense of wanting to recreate that street-market haggling feel we’d seen over the last few play sessions.

After chat, the next question was how to display the things that people were chatting about: the resources available for trade, the deals that were being offered. What should information should be shared between players and what should be hidden? Where should this information be displayed and how?

In about an hour we had thumbnail sketches of every major element in the game. But before we could dive into development, there was one more thing we really needed to test.

Mauricio, we need to see if this chat-based play can really work. We want players to haggle and schmooze and panic about their trades, but will players behave that way when they’re staring at a bank of chat windows?

As close to the real thing:

Off-the-shelf prototyping

You can test many ideas simply by building a rough mock-up using off-the-shelf components. For the trader game, we wanted to test the idea that players in different locations, using only chat, would compete in a trading game, have a good time and develop some kind of relationship with the other players.

To test this we only needed a chat client and a spreadsheet, both of which are readily available form Google. So we scheduled a 30 minute playtest between Liquid Interactive and Macquarie University staff, with everyone signed up to Google Chat and their own Google spreadsheet, and Mauricio and Andrew playing banker/moderator at each location.

The results were great. Players were very focused, chatting in multiple windows simultaneously, closing deals, trying different strategies.

At first the play was very quiet, which was a good sign: it meant that they were completely focused on the chat windows and didn’t feel the need to talk to the players sitting next to them. But even better, as the game went on the players started to either rant or cackle as it became clear that some strategies were working and some weren’t.

When the game wrapped up and players learned their rankings, there was even more wailing and gnashing of teeth because some players who thought they were smoking-hot discovered that they really weren’t all that after all. Everyone laughed, and when we had a conference call debrief there was a lot of warmth and rapport and story-telling between the two groups of players, again a confirmation of the design direction.

So with one final prototype we had tested our final assumptions, we had given ourselves the best chance of success, and we were ready to start development.

A million critical details:

Resolving interface and interactions

Even with all the big pieces in place, amazing how many detailed and critical questions remained to be resolved. The issue of chat windows was a big one:

- How many chat windows can be open at one time?

- If more than one, how do they tile?

- Is there a group chat window, or only individual windows?

- What if you want to have talk to more than one person simultaneously?

- Can players create new chat windows for different groups?

- How should you be notified that someone wants to chat with you?

- How do you move from chatting trading?

All this led into the complexities of real-time trades:

- How do we determine when a trade is complete?

- What is the process for cancelling a trade?

- How do you stop someone changing terms after another party has accepted?

We had endless lists like these, all fiddly and inter-connected.

However, the LI development team resolved all these questions and more, meticulously building up a design specification based on the initial sketches and workflows, and handing detailed wireframes to the design team, who created an elegant but playful UI. However, one big question that sat outside this functional work was how pretty the game should look.

The importance of eye-candy:

Creating an art style

Well into the project we still had these occasional conversations about how this game should be like Settlers of Catan.

It needs to look more like Settlers of Catan!

But Mauricio, the game is nothing like Settlers. You don’t harvest resources, you don’t capture territory. It’s more like the stock market. You watch numbers and you trade.

But that’s not fun!

At the heart of this conversation is again the need to figure out what is fun in a game. Some of us thought the game interface should be data heavy, like a spreadsheet with groovy icons and colours, because this would offer the greatest information density and make it easiest for the player to actually play.

Mauricio, on the other hand, really wanted to see an island with hills and trees and oceans, and little flags or characters marking the countries.

But Mauricio there is no point to a map! Players can’t do anything with it! We can’t show other players’ resources, we can’t show their scores. It’s just wallpaper!

The game won’t be fun if there’s no map!

As it turns out, Mauricio was right. Sure, players can’t do anything with the map, but what’s important is that it stimulates their imaginations. By creating a world, we hook the players’ attention, get them emotionally involved, and frame the experience as something fun and imaginative. This gets them playing and keeps them playing.

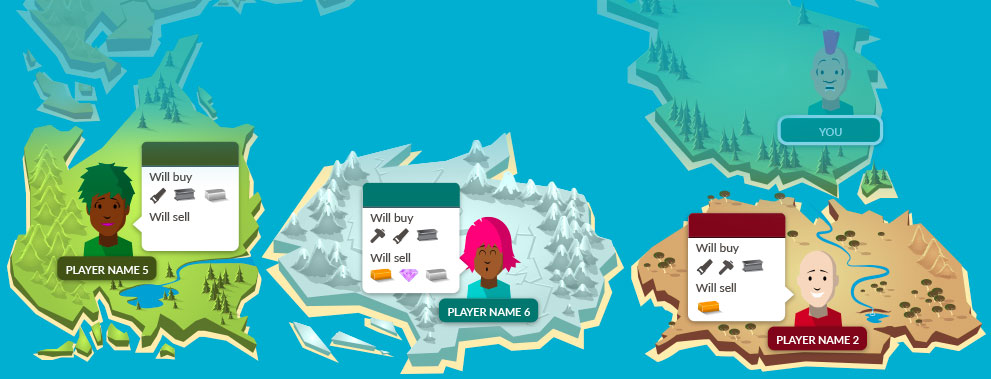

So the LI design team produced a Catan-style island arrangement, and to give it some utility in the game we made dynamic trading arrows that show trades taking place between players. But the real reason why the map works is that when players see all the colours and characters, they immediately think they are about to do something fun.

So the game was well thought-out and looking good, but would it actually work?

The invisible part:

Making a tight and powerful back-end

There’s no easy way around it: multiplayer games are hard to build, and one that works in realtime is even harder. All player actions have to be relayed to a server and then back to each player device. Everything has to be kept up to date. If a player drops out they have to be able to get back into the game quickly. The chat system needs to work on every device and not be bothered about firewalls if possible. Luckily the LI development team are good at finding the right technology and being selective in its application to deliver something that works. Using a combination of MongoDB, Node.js and HTML5, we built a sweet, tight system and delivered it bang on the due date.

The results

While the game has been successful with the target audience of students in Macquarie University’s new online economics course, one of the most surprising uses for the game has turned out to be as an outreach activity for high school students. When the faculty of Business and Economics hosts visits from high schools, this game is one of the most popular activities: engaging the students, generating some warmth and enthusiasm for Macquarie, and facilitating genuinely interesting discussions about international trade.

And as a nice little bonus, Traders of Macquarie won the 2014 NSW iAward for Education.

Design thoughts

One of the best things about this project was the way we developed the interface design and art style at the same time, starting from two ends and working to meet in the middle. This really helped us get the most out of each design element, but also meant that they worked together and complemented each other beautifully.

Management and Development thoughts

The interesting take from this project is the pragmatism that went into creating this game. The very close communication lines between everyone, and on-the-spot discussions about actual issues with actual solutions being proposed and decided on.

This project was very compact and dense in exchange of ideas and materials. The design process was pragmatic and went hand-in-hand with the functional decision-making. Both of these were done side-by-side, in parallel, instead of deciding on function and then designing around it. That same pragmatism went into creating the technology for this, very minimal and to the point. We chose tools and methods based on requirements, instead of the other way around.

Client thoughts

I was in search for a company that would be able to develop this game, and when I contacted Liquid Interactive I always had a feeling that they understood what I was trying to achieve. It went beyond design specifications; it was a mutual understanding of the goal. It was easier for me to explain what I wanted to achieve, than try to explain what the software should do. Having this team as a soundboard to guide what the game was trying to achieve was really good, and after every conversation I felt reassured that we were heading in the right direction.

The objective was simple: a game that was fun, would help students break the ice, and common experience that the convener could point to illustrate his points. I could say we achieved that and much more thanks to these guys.

Side note: A bonus was that the game can be played many times by the same players and it is always different. I can also tell you that as the creator of the game I have never won the game (maybe that says a lot about my negotiation skills).